Big Brains Helped Large Animals Survive Extinction

TAU researchers: more brain power helped animals adapt to changing conditions and increased chances of survival.

What do an elephant, a rhino and a hippopotamus all have in common? All three, along with other large animals, survived the mass extinction that took place for a period of about 120,000 years, starting from the time the last Ice Age began. In contrast, other huge animals, such as giant armadillos (weighing a ton), giant kangaroos and mammoths went extinct.

Researchers at Tel Aviv University and the University of Naples have examined the mass extinction of large animals over the past tens of thousands of years, and found that those species who survived extinction had, on average, much larger brains than those who did not. The researchers conclude that having a large brain (relative to body size) indicates relatively high intelligence and helped the surviving species adapt to changing conditions and cope with potential causes of extinction, such as human hunting.

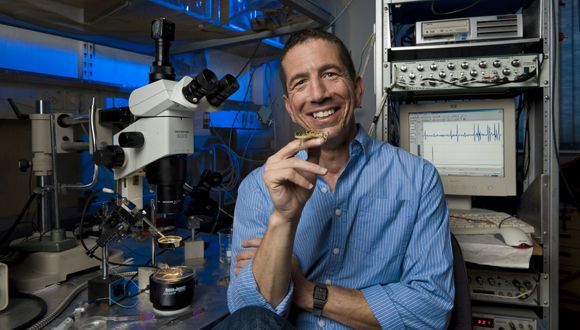

The study was led by doctoral student Jacob Dembitzer of the University of Naples in Italy, Prof. Shai Meiri of Tel Aviv University’s School of Zoology and The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, and Prof. Pasquale Raia and doctoral student Silvia Castiglione of the University of Naples. The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Heavy Weight – No Guarantee

The researchers explain that the last Ice Age was characterized by the widespread extinction of large and giant animals on all continents on earth (except Antarctica). Among these:

- America: Giant ground sloths weighing 4 tons, a giant armadillo weighing a ton, and mastodons

- Australia: Marsupial diprotodon weighing a ton, giant kangaroos, and a marsupial ‘lion’

- Eurasia: Giant deer, woolly rhinoceros, mammoth, and giant elephants weighing up to 11 tons

Other large animals, however, such as elephants, rhinos, and hippos, survived this extinction event and exist to this day.

The researchers also note that in some places, the extinction was particularly widespread:

- Australia: The red and grey kangaroos are today the largest native animals

- South America: The largest survivors are the guanaco and vicuña (similar to the llama, which is a domesticated animal) and the tapir, while many of the species weighing half a ton or more have become extinct

Brains over Body

Jacob Dembitzer: “We know that most of the extinctions were of large animals, and yet it is not clear what distinguishes the large extant species from those that went extinct. We hypothesized that behavioral flexibility, made possible by a large brain in relation to body size, gave the surviving species an evolutionary advantage – it has allowed them to adapt to the changes that have taken place over the last tens of thousands of years, including climate change and the appearance of humans. Previous studies have shown that many species, especially large species, went extinct due to over-hunting by humans that have entered their habitats. In this study, we tested our hypothesis for mammals over a period of about 120,000 years, from the time the last Ice Age began, and the time that modern man began to spread all over the world with lethal weapons, to 500 years before our time. This hypothesis even helps us explain the large number of extinctions in South America and Australia, since the large mammals living on these continents had relatively small brains.”

The researchers collected data from the paleontological literature on 50 extinct species of mammal from all continents, weighing from 11 kg (an extinct giant echidna) up to 11 tons (the straight-tusked elephant, which was also found in the Land of Israel), and compared the size of their cranial cavity to that of 291 evolutionarily close mammal species that survived and exist today, weighing from 1.4 kg (the platypus) up to 4 tons (the African elephant). They fed the data into statistical models that included the weighting of body size and phylogeny between different species.

Prof. Meiri: “We found that the surviving animals had brains 53% larger, on average than evolutionarily closely related, extinct species of a similar body size. We hypothesize that mammals with larger brains have been able to adapt their behavior and cope better with the changing conditions – mainly human hunting and possibly climate changes that occurred during that period – compared to mammals with relatively small brains.”

Related posts

Over the Past 1.5 Million Years, Human Hunting Preferences have Wiped Out Large Animals