A new study at Tel Aviv University found that sponges in the Gulf of Eilat have developed an original way to keep predators away. The researchers found that the sponges contain an unprecedented concentration of the highly toxic mineral molybdenum (Mo). In addition, they identified the bacterium that enables sponges to store such high concentrations of this precious metal and unraveled the symbiosis between the two organisms. The study was led by PhD student Shani Shoham and Prof. Micha Ilan from TAU’s School of Zoology. The paper was published in the leading journal Science Advances.

Two Ph.D. candidate Shani Shoham (right) and Raz Marom (Moskovich) happy to finally collect a sponge sample (in the bag) after several dives.

The researchers explain that sponges are the earliest multicellular organisms known to science. They live in marine environments and play an important role in the earth’s carbon, nitrogen, and silicon cycles. A sponge can process and filter seawater 50,000 times its body weight daily. With such enormous quantities of water flowing through them, they can accumulate various trace elements – and scientists try to understand how they cope with toxic amounts of materials like arsenic and molybdenum.

The Hidden Shine of the Sponge

PhD student Shani Shoham: “20 to 30 years ago, researchers from our lab collected samples of a rare sponge called Theonella conica from the coral reef of Zanzibar in the Indian Ocean and found a high concentration of molybdenum. Molybdenum is a trace element, important for metabolism in the cells of all animals including humans, and widely used in industry. In my research, I wanted to test whether such high concentrations are also found in this sponge species in the Gulf of Eilat, where it grows at depths of more than 27 meters. Finding the sponge and analyzing its composition I discovered that it contained more molybdenum than any other organism on earth: 46,793 micrograms per gram of dry weight.”

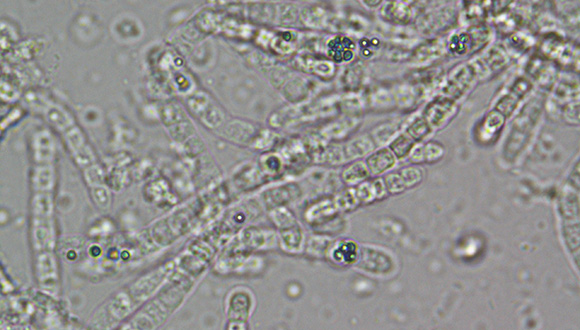

Here’s what it looks like under a light microscope: Molybdenum accumulation in the bacterium Entotheonella. You can see the blue in the vacuoles. (Photo: Shani Shoham).

Shoham adds: “Like all trace elements, molybdenum is toxic when its concentration is higher than its solubility in water. But we must remember that a sponge is essentially a hollow mass of cells with no organs or tissues. Specifically in Theonella conica, up to 40% of the body volume is a microbial society – bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in symbiosis with the sponge. One of the most dominant bacteria, called Entotheonella sp., serves as a ‘detoxifying organ’ for accumulating metals inside the body of its sponge hosts. Hoarding more and more molybdenum, the bacteria convert it from its toxic soluble state into a mineral”.

“We are not sure why they do this. Perhaps the molybdenum protects the sponge, by announcing: “I’m toxic! Don’t eat me!”, and in return for this service the sponge does not eat the bacteria and serves as their host”

Sponge Bling: The Search for Molybdenum

Molybdenum is in high demand, mostly for alloys (for example, high-strength steel). Still, according to Shoham, it would be impracticable to retrieve it from sponges. The concentration is very high, but when translated into weight we could only get a few grams from every sponge, and the sponge itself is relatively rare. Sponges are grown in marine agriculture, mostly for the pharmaceutical industry, but this is quite a challenging endeavor. Sponges are very delicate creatures that need specific conditions”.

Shoham continues: “On the other hand, future research should focus on the ability of Entotheonellasp. bacteria to accumulate toxic metals. A few years ago, our lab discovered huge concentrations of other toxic metals, arsenic (As) and barium (Ba), in a close relative of Theonella conica, called Theonella swinhoei, which is common in the Gulf of Eilat. In this case, too, Entotheonellawas found to be largely responsible for hoarding the metals and turning them into minerals, thereby neutralizing their toxicity. Continued research on the bacteria can prove useful for treating water sources polluted with arsenic, a serious hazard which directly affects the health of 200 million people worldwide”.

Prof. Micha Ilan.