Let Them Migrate in Peace

Migratory birds in times of war.

Israel, a stopover for over 500 million migratory birds heading to warmer lands, has been at war on multiple fronts for a year. As these birds migrate south, they face not only the usual dangers but also added risks from fighter jets, missiles, and UAVs along their northern arrival routes and southern destinations.

Prof. Yossi Leshem from the School of Zoology at the George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences has studied birds, especially migratory ones, for over 50 years. He began tracking their flight paths in Israel 40 years ago using a glider, observing their spring migration from Egypt to Lebanon and autumn route southward. This work allowed him to map their arrival times, flight altitudes, and the effects of weather on their behavior.

Flying with the Birds (Photo: Eyal Bartov).

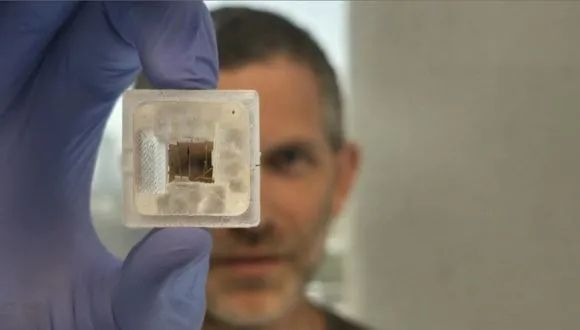

In the 1980s, he pioneered radar use in Israel to study bird migration, working with the Israeli Air Force to reduce mid-air collisions between military aircraft and birds. We asked him how the current conflict impacts migratory birds and whether solutions exist to protect both human and avian lives.

Can Radar Distinguish Between Birds and Aircraft?

“A radar is an electronic device that sends out electromagnetic waves. If there’s something in the air, the waves bounce back, indicating distance and azimuth. The larger the bird, the stronger the radar signal. Large birds like raptors, pelicans, storks, or cranes are at greater risk, posing the most significant danger to Air Force planes”, explains Prof. Leshem.

Doing everything to prevent an air collision with them. Pelicans in tight formation during their autumn migration (Photo: Aharon Shimshon).

“Today, it’s understood that larger birds generally fly over land to use thermals (warm air rising from the ground). Based on their speed, we can often identify flocks of birds. We can track migratory birds on radar up to 80-90 kilometers away”, says Prof. Leshem. However, since the war began and UAVs from Lebanon started appearing, distinguishing birds from hostile aircraft has become more challenging.

“During autumn, migration comes through Europe, Turkey, Lebanon, and down through Israel—the same route used by missiles and UAVs. They come from the same direction, height, and azimuth”. According to Prof. Leshem, this has led to four main challenges: additional pressure on air defense and the air force, which must quickly decide if there is a true threat or if cranes are merely passing by; stress for civilians prompted by alert systems when stork flocks fly overhead; harm to wildlife entering Israeli airspace; and substantial financial costs of interception missiles and air force resources”. Nonetheless, Prof. Leshem reveals that efforts are underway to develop a system that can differentiate between birds and UAVs, which will save countless bird lives.

Protecting Israel’s Residents, Endangering Its Birds: The Iron Dome System.

How is the War Affecting Local Birds?

It’s not just migratory birds suffering from the consequences of war. Prof. Leshem leads a project in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture and the Society for the Protection of Nature, using barn owls and kestrels for natural rodent control in agricultural areas to reduce pesticide use. There are about 5,000 nesting boxes nationwide, supported by hundreds of farmers who receive professional assistance. The project now includes ten Middle Eastern countries and has recently welcomed Georgia, Ukraine, and Germany, fostering cross-border cooperation.

Prof. Leshem explains that barn owls typically lay between 5 to 12 eggs annually, depending on food availability. “However, the war has significantly reduced nesting and egg-laying in conflict zones in the north and south, where burned fields have impacted rodent populations. Fewer chicks this year will lead to a smaller barn owl population next year, resulting in long-term effects”.

A Death Trap for Rodents – A Cut in Food Supply for Birds of Prey: Burned Fields in the Gaza Border Area.

Will the Impact on Birds Affect the Entire Ecological Balance?

“Absolutely, the impact on birds is affecting the entire ecological balance in several ways. From small songbirds to larger migratory birds like storks, each species plays a crucial role in the ecosystem. For example, the black-headed bunting migrates from this region to Africa in the fall, crossing the Sahara Desert, and depends on the insects in our fields and surroundings to build up enough fat reserves for the journey. If these fields aren’t providing enough food, the bunting may seek other locations, leading to an increase in insects in our agricultural areas, which can harm local crops”.

“Additionally, storks, which arrive here in large numbers and help control rodent populations by preying on voles in flooded fields, are essential for maintaining this balance. If these storks don’t arrive, farmers may face increased rodent populations, which can damage crops. So, if birds don’t receive the ecological support they need here, the local balance will likely shift significantly, bringing widespread environmental consequences for agriculture, species diversity, and our overall environmental health”, he explains.

On its way to Africa, stopping to refuel in Israel: the Black-headed Bunting.

Will Migration Patterns Shift Due to War?

“Migration has been occurring for hundreds of thousands of years, and it won’t change quickly,” assures Professor Leshem. “However, it could impact survival chances. In a typical winter, about 50,000 cranes spend the season in the Hula Valley, but last year only 15,000 arrived. Some birds, like storks, birds of prey, and pelicans, stop here for just a night or two to ‘refuel’ before continuing their journey. If they can’t land in their usual spots due to burned fields or are scared off by gunfire, they may need to find other locations. This search could decrease their chances of successfully reaching their destination, affecting the larger migration cycle”.

Perhaps there will still be beautiful days ahead. Thousands of cranes in the Hula Lake (Photo: Shiraz Pashinsky).

Related posts

“I Applied to Several Universities, But TAU’s Documentary Film Program Stood Out”