The World’s Oldest Grilled Fish Recipe

International team, including leading Israeli universities, finds oldest evidence of the controlled use of fire to cook food.

The question of how early humans began using fire to cook food has been the subject of much scientific discussion for over a century. Cooking is defined as the ability to process food by controlling the temperature at which it is heated and includes a wide range of methods. Until now, the earliest evidence of cooking dates to approximately 170,000 years ago.

Recent findings shed new light on the matter: A remarkable scientific discovery has been made by researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU), Tel Aviv University (TAU), and Bar-Ilan University (BIU), in collaboration with the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Oranim Academic College, the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research (IOLR) institution, the Natural History Museum in London, and the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, namely: the remains of a carp-like fish found at the Gesher Benot Ya’aqov (GBY) archaeological site in Israel, which were analyzed closely and were found to have been cooked roughly 780,000 years ago.

“These new findings demonstrate not only the importance of freshwater habitats and the fish they contained for the sustenance of prehistoric man, but also illustrate prehistoric humans’ ability to control fire in order to cook food, and their understanding the benefits of cooking fish before eating it.” Dr. Irit Zohar and Dr. Marion Prevost

Plenty of Fish and a Culinary Revolution

The study was led by a team of researchers: Dr. Irit Zohar, a researcher at TAU’s Steinhardt Museum of Natural History and curator of the Beit Margolin Biological Collections at Oranim Academic College, and Hebrew University Professor Naama Goren-Inbar, director of the excavation site. The research team also included Dr. Marion Prevost at HU’s Institute of Archaeology; Prof. Nira Alperson-Afil at BIU’s Department for Israel Studies and Archaeology; Dr. Jens Najorka of the Natural History Museum in London; Dr. Guy Sisma-Ventura of the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute; Prof. Thomas Tütken of the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz and Prof. Israel Hershkovitz at TAU’s Faculty of Medicine.

The findings were published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

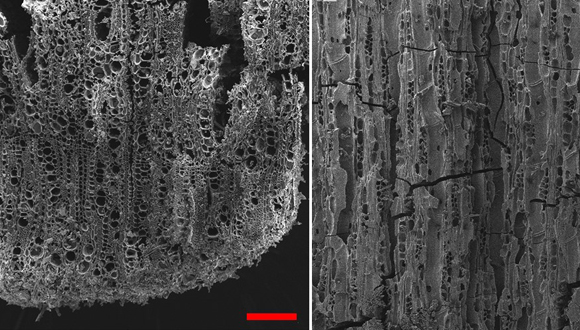

In the study, the researchers focused on pharyngeal teeth (used to grind up hard food such as shells) belonging to fish from the carp family. These teeth were found in large quantities at different archaeological strata at the site. By studying the structure of the crystals that form the teeth enamel (whose size increases through exposure to heat), the researchers were able to prove that the fish caught at the ancient Hula Lake, adjacent to the site, were exposed to temperatures suitable for cooking, and were not simply burned by a spontaneous fire.

Until now, evidence of the use of fire for cooking had been limited to sites that came into use much later than the GBY site–by some 600,000 years, and ones most are associated with the emergence of our own species, homo sapiens.

An example of a skull of modern carp from the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History

“This study demonstrates the huge importance of fish in the life of prehistoric humans, for their diet and economic stability,” explains Dr. Irit Zohar and Dr. Marion Prevost. “Furthermore, by studying the fish remains found at Gesher Benot Ya’aqob in Israel we were able to reconstruct, for the first time, the fish population of the ancient Hula Lake and to show that the lake held fish species that became extinct over time. These species included giant barbs (carp like fish) that reached up to 2 meters in length. The large quantity of fish remains found at the site proves their frequent consumption by early humans, who developed special cooking techniques. These new findings demonstrate not only the importance of freshwater habitats and the fish they contained for the sustenance of prehistoric man, but also illustrate prehistoric humans’ ability to control fire in order to cook food, and their understanding the benefits of cooking fish before eating it.”

“The fact that the cooking of fish is evident over such a long and unbroken period of settlement at the site indicates a continuous tradition of cooking food,” adds Prof. Naama Goren-Inbar. “This is another in a series of discoveries relating to the high cognitive capabilities of the Acheulian hunter-gatherers who were active in Israel’s ancient Hula Valley region. These groups were deeply familiar with their environment and the various resources it offered them.”

“Further, it shows they had extensive knowledge of the life cycles of different plant and animal species,” adds Prof. Goren-Inbar. “Gaining the skill required to cook food marks a significant evolutionary advance, as it provided an additional means for making optimal use of available food resources. It is even possible that cooking was not limited to fish, but also included various types of animals and plants.”

Evolutionary Leap

Prof. Hershkovitz and Dr. Zohar note that the transition from eating raw food to eating cooked food had dramatic implications for human development and behavior.

Eating cooked food reduces the bodily energy required to break down and digest food, allowing other physical systems to develop. It also leads to changes in the structure of the human jaw and skull. This change freed humans from the daily, intensive work of searching for and digesting raw food, providing them free time in which to develop new social and behavioral systems. Some scientists view eating fish as a milestone in the quantum leap in human cognitive evolution, providing a central catalyst for the development of the human brain. They claim that eating fish is what made us human.

Even today, it is widely known that the contents of fish flesh, such as omega-3 fatty acids, zinc, iodine and more, contribute greatly to brain development.

“These groups made use of the rich array of resources provided by the ancient Hula Valley and left behind a long settlement continuum with over 20 settlement strata.” Prof. Naama Goren-Inbar

Settled Down Where There Was Food

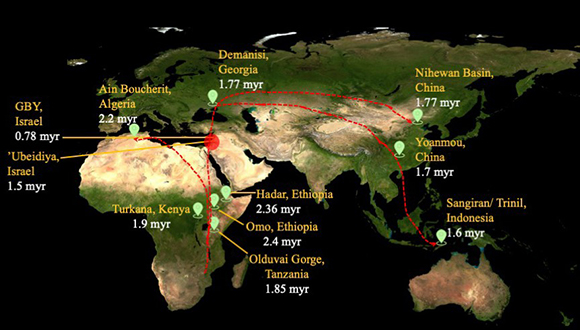

The research team believe that the location of freshwater areas, some of them in areas that have long since dried up and become arid deserts, determined the route of the migration of early man from Africa to the Levant and beyond. Not only did these habitats provide drinking water and attracted animals to the area but catching fish in shallow water is a relatively simple and safe task with a very high nutritional reward.

The team posits that exploiting fish in freshwater habitats was the first step on prehistoric humans’ route out of Africa. Early man began to eat fish around 2 million years ago but cooking fish—as found in this study—represented a real revolution in the Acheulian diet and is an important foundation for understanding the relationship between man, the environment, climate, and migration when attempting to reconstruct the history of early humans.

HU’s Goren-Inbar added that the archaeological site of GBY documents a continuum of repeated settlement by groups of hunter-gatherers on the shores of the ancient Hula Lake which lasting tens of thousands of years. “These groups made use of the rich array of resources provided by the ancient Hula Valley and left behind a long settlement continuum with over 20 settlement strata,” Goren-Inbar explained. The excavations at the site have uncovered the material culture of these ancient hominins, including flint, basalt, and limestone tools, as well as their food sources, which were characterized by a rich diversity of plant species from the lake and its shores (including fruit, nuts, and seeds) and by many species of land mammals, both medium-sized and large.

Location of Gesher Benot Ya’aqov (GBY) archeological site on Home erectus route out of Africa

“This study of isotopes is a real breakthrough, as it allowed us to reconstruct the hydrological conditions in this ancient lake throughout the seasons, and thus to determine that the fish were not a seasonal economic resource but were caught and eaten all year round. Thus, fish provided a constant source of nutrition that reduced the need for seasonal migration.” Dr. Guy Sisma-Ventura

Playing With Fire

It should be noted that evidence of the use of fire at the site—the oldest such evidence in Eurasia—was identified first by BIU’s Prof. Nira Alperson-Afil. “The use of fire is a behavior that characterizes the entire continuum of settlement at the site,” she explained. “This affected the spatial organization of the site and the activity conducted there, which revolved around fireplaces.” Alperson-Afil’s research of fire at the site was revolutionary for its time and showed that the use of fire began hundreds of thousands of years before previously thought.

“In this study, we used geochemical methods to identify changes in the size of the tooth enamel crystals, as a result of exposure to different cooking temperatures,” explained Dr. Jens Najorka of the Natural History Museum in London. “When they are burnt by fire, it is easy to identify the dramatic change in the size of the enamel crystals, but it is more difficult to identify the changes caused by cooking at temperatures between 200 and 500 degrees Celsius. The experiments I conducted with Dr. Zohar allowed us to identify the changes caused by cooking at low temperatures. We do not know exactly how the fish were cooked but given the lack of evidence of exposure to high temperatures, they were not cooked directly in fire and were not thrown into a fire as waste or as material for burning.”

Dr. Guy Sisma-Ventura of the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute and Prof. Thomas Tütken of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz were also part of the research group, providing analysis of the isotope composition of oxygen and carbon in the enamel of the fishes’ teeth: “This study of isotopes is a real breakthrough, as it allowed us to reconstruct the hydrological conditions in this ancient lake throughout the seasons, and thus to determine that the fish were not a seasonal economic resource but were caught and eaten all year round. Thus, fish provided a constant source of nutrition that reduced the need for seasonal migration.”

The Israeli research team (from left to right): Dr. Irit Zohar, Dr. Marion Prévost, Prof. Naama Goren, Dr. Guy Sisma-Ventura, Prof. Nira Alperson-Afil, Prof. Israel Hershkovitz

Investigating a pile of industrial waste mixed with charcoal on Slaves’ Hill, Timna Valley (photo: Erez Ben-Yosef and the Central Timna Valley Project)

The researchers explain that Timna’s copper industry was

Investigating a pile of industrial waste mixed with charcoal on Slaves’ Hill, Timna Valley (photo: Erez Ben-Yosef and the Central Timna Valley Project)

The researchers explain that Timna’s copper industry was  Excavating Slaves’ Hill (photo: Hai Ashkenazi, courtesy of the Central Timna Valley Project)

Mark Cavanagh describes the findings: “We found significant changes in the composition of the charcoal as time went on. Charcoal from the bottom layer of the mounds, dated to the 11th century BCE, mostly contained two plants known to be excellent burning materials: 40% acacia thorn trees, and 40% local white broom, including broom roots. The ‘burning coals of the broom tree’ are even mentioned in the Bible as excellent firewood (Psalm 120, 4). About 100 years later, around the middle of the 10th century BCE, we saw a change in the makeup of the charcoal. The industry had begun to use fuel of a lower quality, such as various desert bushes and palm trees. In this latter stage, other trees were imported from far away, such as junipers from the Edomite plateau in present-day Jordan, covering distances of up to 100 km from Timna, and terebinth, also transported from dozens of kilometers away.”

Excavating Slaves’ Hill (photo: Hai Ashkenazi, courtesy of the Central Timna Valley Project)

Mark Cavanagh describes the findings: “We found significant changes in the composition of the charcoal as time went on. Charcoal from the bottom layer of the mounds, dated to the 11th century BCE, mostly contained two plants known to be excellent burning materials: 40% acacia thorn trees, and 40% local white broom, including broom roots. The ‘burning coals of the broom tree’ are even mentioned in the Bible as excellent firewood (Psalm 120, 4). About 100 years later, around the middle of the 10th century BCE, we saw a change in the makeup of the charcoal. The industry had begun to use fuel of a lower quality, such as various desert bushes and palm trees. In this latter stage, other trees were imported from far away, such as junipers from the Edomite plateau in present-day Jordan, covering distances of up to 100 km from Timna, and terebinth, also transported from dozens of kilometers away.”

Tel Aviv University’s Dr. Dafna Langgut and Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef

Tel Aviv University’s Dr. Dafna Langgut and Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef

Vessels intended to accompany the dead into the afterlife. These Cypriot jugs and juglets were laid on the deceased. Remains of opium were found in several of the vessels (photo: Assaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Vessels intended to accompany the dead into the afterlife. These Cypriot jugs and juglets were laid on the deceased. Remains of opium were found in several of the vessels (photo: Assaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)