Ancient Climate Crisis Transformed Us from Nomadic Hunters to Settled Farmers

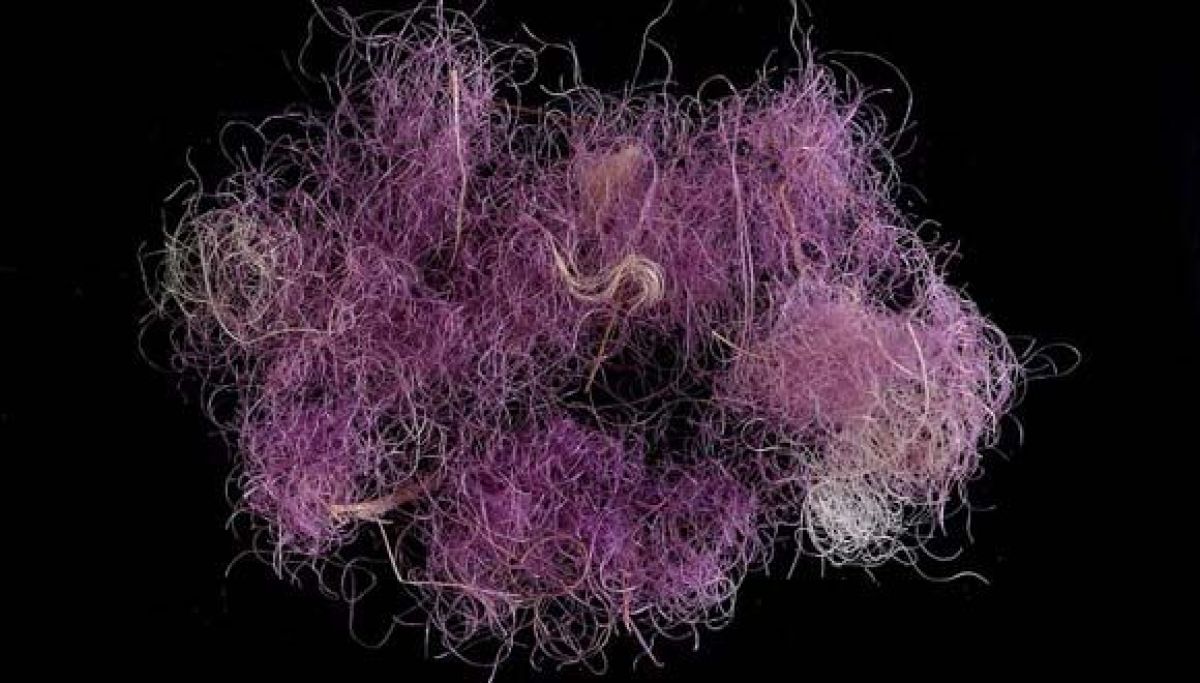

Researchers used plant remains to reconstruct the climate in the Southern Levant at the end of the last ice age.

What made the residents in the Southern Levant, tens of thousands of years ago, put down their walking sticks and hunting gear and instead become settled farmers? Apparently, it was the result of a climate crisis that took place at the end of the last ice age, about 10,000 to 20,000 years ago.

A new record of significant climate changes in the region, based on the identification of ancient plant remains, sheds light on the dramatic transition. Against the background of the Glasgow Climate Change Summit, the researchers believe that understanding the response of the region’s flora to the dramatic past climate changes can help in preserving the regional variety of plant species and in planning for current and future climate challenges.

The Crisis that Marched Humanity Forward

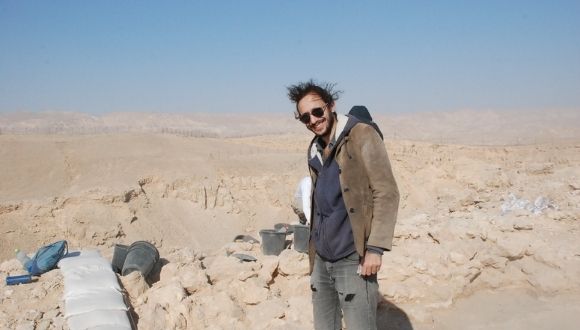

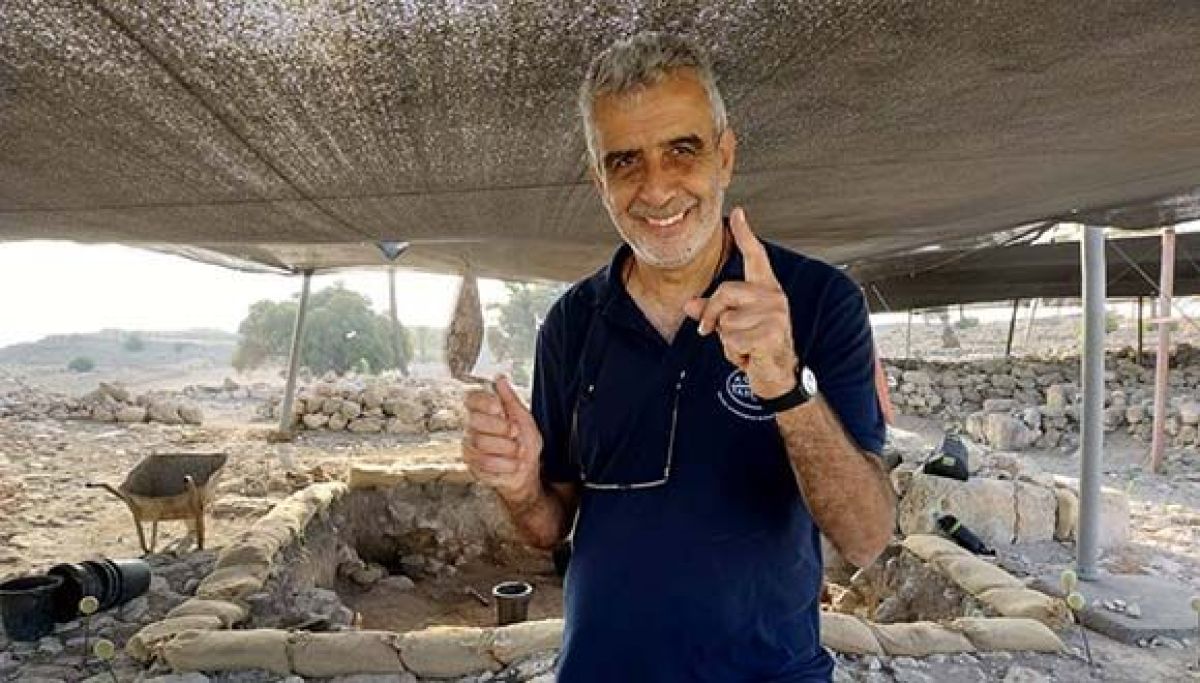

The research was conducted by Dr. Dafna Langgut of the Department of Archaeology and The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University; Prof. Gonen Sharon, Head of the MA Program in Galilee Studies at Tel-Hai College, and Dr. Rachid Cheddadi, expert in evolution and palaeoecology of University of Montpellier, Institute of Evolutionary Sciences (ISEM) Montpellier, France. The groundbreaking study was recently published in the leading scientific journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

The study was conducted at the prehistoric archaeological site Jordan River Dureijat (“Jordan River Stairs”) on the shores of the ancient Lake Hula. The site is unique for its exceptional preservation conditions yielding finds that enabled discovery of the primary activity of its early local residents – fishing. Preserved botanic remains also enabled researchers to identify the plants that grew 10,000 – 20,000 years ago in the Hula Valley and its surroundings.

The prehistoric archaeological site Jordan River Dureijat (“Jordan River Stairs”) on the shores of the Paleo Lake Hula

Two major processes in world history took place during this period, the first of which was the transition from a nomadic to a settled lifestyle that occurs during a period of dramatic climate change. Prof. Sharon, supervisor of the Madregot Hayarden (“Jordan Stairs”) excavation, explains: “In the study of prehistory, this period is called the Epipalaeolithic period. At its outset, people were organized in small groups of hunter-gatherers who roamed the area. Then, about 15,000 years ago, we are witness to a significant change in lifestyle: the appearance of settled life in villages, and additional dramatic processes that reach their apex during the Neolithic period that followed. This is the time when the most dramatic change of human history occurred – the transition to the agricultural way of life that shaped the world as we know it today.”

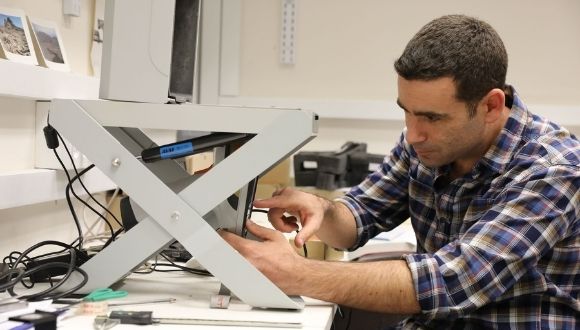

Dr. Langgut, an archaeobotanist specializing in identification of plant remains, elaborates on the second dramatic process of this period, namely the climatic changes that occurred in the region. “Although at the peak of the last ice age, about 20,000 years ago, the Mediterranean Levant was not covered with an ice sheet as in other parts of the world, the climatic conditions that existed nevertheless differed from those of today. Their exact characteristics were unclear until this study. The climatic model that we built is based on reconstruction of the fluctuation of the spread of plant species indicating that the main climatic change in our area is expressed by a drop in temperature (up to five degrees Celsius less than today), whereas the precipitation amounts (rain, snow, sleet, or hail) were close to those of today (only about 50 mm less than today’s annual average).

Dr. Dafna Langgut

Temperature Fluctuations

However, Dr. Langgut explains that about 5,000 years later, in the Epipalaeolithic period (about 15,000 years ago) a significant improvement in climate conditions can be seen in the model. An increased prevalence of heat-tolerant tree species, such as olive, common oak, and Pistacia, indicate an increase in temperature and precipitation.

During this period, the first sites of the Natufian culture appear in our region. It could very well be that the temperate climate assisted in the development and flourishing of this culture, in which permanent settlement, stone structures, food storage facilities, and more first appear on the global stage.

The next stage of the study deals with the end of the Epipalaeolithic period, about 11,000-12,000 years ago, known globally as the Younger Dryas period. This period is characterized by a return to a cold, dry climate like that of the ice age, causing somewhat of a climate crisis around the world. The researchers claim that until this study, it was unclear whether and to what extent there was any expression of this period in the Levantine region.

Little Rain, but Throughout the Year

According to the researchers: “The findings that arise from the climate model presented in the article show that the period was characterized by climatic instability, intense fluctuations, and a considerable drop in temperatures. Nevertheless, while reconstructing the precipitation, a surprising phenomenon was discovered: the average quantities of rainfall reconstructed were only slightly less than those of today; however, the precipitation was distributed over the entire year, including summer rains.”

The researchers claim that such distribution assisted in the expansion and thriving of annual and leafy plant species. The gatherers who lived in this period now had a wide, readily available variety of gatherable plants throughout the entire year. This variety enabled their familiarity just before domestication. The researchers are of the opinion that these findings contribute to a new understanding of the environmental changes that took place on the eve of the transition to agriculture and domestication of animals.

Summary

Why did humans settle down and start farming the land? While this study doesn’t fully answer this questions, it does reconstruct the climate in what is today Israel from 20,000 to 10,000 years ago, revealing the dramatic environmental and climatic changes that uniquely combined with social and technological innovations 12,000 years ago and formed the background for the development of acriculture in the Levant.

The warmer, more humid climate between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago coincided with the Natufian culture, and may have supported their practice of living in one place for a long time, thanks to increased gathering and storage opportunities. Around 13,000 years ago, temperatures sunk a bit and rains would fall throughout the year, favoring open-field vegetation and plants. 12,000 years ago, the Holocene (the current geological era) began, which in the Near East meant long hot and dry summers necessitating gathering and storing food during winter and spring. The new environmental conditions pushed people to make greater efforts to domesticate, farm and store their crops – setting the stage for the Neolithic revolution.

Dr. Langgut concludes: “This study contributes not only to understanding the environmental background for momentous processes in human history such as the first permanent settlement and the transition to agriculture, but also provides information on the history of the region’s flora and its response to past climatic changes. There is no doubt that this knowledge can assist in preserving species variety and in meeting current and future climate challenges.”

Dr. Dafna Langgut collects sediment samples for pollen investigation.

Featured image: An Israeli farmer in his vineyard

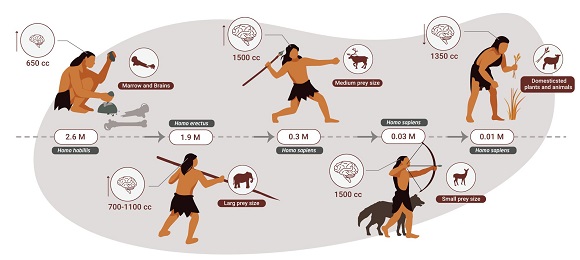

The multidisciplinary reconstruction conducted by TAU researchers for almost a decade proposes a complete change of paradigm in the understanding of human evolution. Contrary to the widespread hypothesis that humans owe their evolution and survival to their dietary flexibility, which allowed them to combine the hunting of animals with vegetable foods, the picture emerging here is of humans evolving mostly as predators of large animals.

“Archaeological evidence does not overlook the fact that stone-age humans also consumed plants,” adds Dr. Ben-Dor. “But according to the findings of this study plants only became a major component of the human diet toward the end of the era.”

Evidence of genetic changes and the appearance of unique stone tools for processing plants led the researchers to conclude that, starting about 85,000 years ago in Africa, and about 40,000 years ago in Europe and Asia, a gradual rise occurred in the consumption of plant foods as well as dietary diversity – in accordance with varying ecological conditions. This rise was accompanied by an increase in the local uniqueness of the stone tool culture, which is similar to the diversity of material cultures in 20th-century hunter-gatherer societies. In contrast, during the two million years when, according to the researchers, humans were apex predators, long periods of similarity and continuity were observed in stone tools, regardless of local ecological conditions.

The multidisciplinary reconstruction conducted by TAU researchers for almost a decade proposes a complete change of paradigm in the understanding of human evolution. Contrary to the widespread hypothesis that humans owe their evolution and survival to their dietary flexibility, which allowed them to combine the hunting of animals with vegetable foods, the picture emerging here is of humans evolving mostly as predators of large animals.

“Archaeological evidence does not overlook the fact that stone-age humans also consumed plants,” adds Dr. Ben-Dor. “But according to the findings of this study plants only became a major component of the human diet toward the end of the era.”

Evidence of genetic changes and the appearance of unique stone tools for processing plants led the researchers to conclude that, starting about 85,000 years ago in Africa, and about 40,000 years ago in Europe and Asia, a gradual rise occurred in the consumption of plant foods as well as dietary diversity – in accordance with varying ecological conditions. This rise was accompanied by an increase in the local uniqueness of the stone tool culture, which is similar to the diversity of material cultures in 20th-century hunter-gatherer societies. In contrast, during the two million years when, according to the researchers, humans were apex predators, long periods of similarity and continuity were observed in stone tools, regardless of local ecological conditions.