How many people in the Kingdom of Judah could read and write? And what does this say about the date of the composition of biblical texts like the Books of Kings? Researchers at Tel Aviv University used state-of-the-art image processing and machine learning technologies and collaborated with senior handwriting examiner to analyze 18 ancient texts from the Tel Arad military post dating back to around 600 BCE. They concluded that they were written by no fewer than 12 authors, a finding suggesting that many of the inhabitants of the kingdom of Judah during that period were able to read and write, with literacy not reserved as an exclusive domain in the hands of a few royal scribes.

Who wrote the books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings?

The special interdisciplinary study was conducted by Dr. Arie Shaus, Ms. Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin, and Dr. Barak Sober of

the Department of Applied Mathematics, Prof. Eli Piasetzky of

the Raymond and Beverly Sackler School of Physics and Astronomy, and Prof. Israel Finkelstein of

the Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archeology and Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations. The forensic handwriting specialist is Ms. Yana Gerber, a senior expert who served for 27 years in the Questioned Documents Laboratory of Israel Police Division of Identification and Forensic Science, and in the police’s International Crime Investigations Unit.

“There is a lively debate among experts as to whether the books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings were compiled in the last days of the kingdom of Judah, or after the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians,” explains Dr. Shaus. “One way to try to get to the bottom of this question is to ask when there was the potential for the writing of such complex historical works. For the period following the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BC, there is a very scant archaeological evidence of Hebrew writing in Jerusalem and its surroundings, whereas for the period preceding the destruction of the Temple, an abundance of written documents has been found. But then the question arises – who wrote these documents? Was this a society with widespread literacy, or was there just a handful of literate people?”

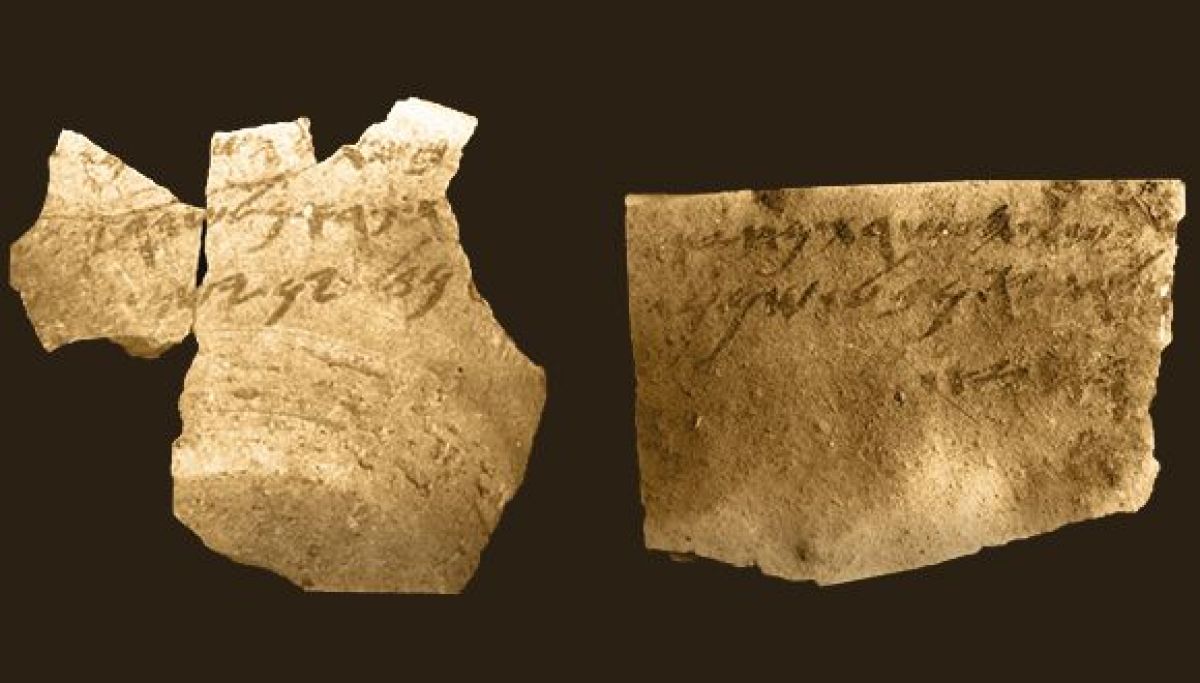

To answer this question, the researchers examined the writings found in Tel Arad – ostraca (fragments of pottery vessels containing ink inscriptions) that were discovered at the Tel Arad site in the 1960s. Tel Arad was a small military post on the southern border of the kingdom of Judah; its built-up area was about two dunams and it housed between 20 and 30 soldiers.

“We examined the question of literacy empirically, from different directions of image processing and machine learning,” says Ms. Faigenbaum-Golovin. “Among other things, these areas help us today with the identification, recognition and analysis of handwriting, signatures, and so on. The big challenge was to adapt modern technologies to 2,600-year-old ostraca. With a lot of effort, we were able to produce two algorithms that could compare letters and answer the question of whether two given ostraca were written by two different people.”

Police detective work following biblical texts

In 2016, the researchers published in

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

(PNAS) that algorithmically, and with high statistical probability, 18 texts – the longest of the Tel Arad inscriptions – were written by at least four different authors. Combined with the textual evidence, the researchers concluded that there were in fact at least six different writers. The study aroused great interest around the world.

Now, in an unprecedent move, the Tel Aviv University researchers have decided to compare the algorithmic methods, which have since been refined, to the forensic approach. To this end, Yana Gerber, a retired superintendent and senior questioned document examiner from the Israel Police Division of Identification and Forensic Science, joined the team. After an in-depth examination of the ancient inscriptions, Ms. Gerber found that the 18 texts were written by at least 12 distinct writers with varying degrees of certainty. Gerber examined the original Tel Arad ostraca at the Israel Museum, the Eretz Israel Museum, the Sonia and Marco Nedler Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, and the Israel Antiquities Authority’s warehouses at Beit Shemesh.

“This study was very exciting, perhaps the most exciting in my professional career,” says Ms. Gerber. “These are ancient Hebrew inscriptions written in ink on shards of pottery, utilizing an alphabet that was previously unfamiliar to me. I studied the characteristics of the writing in order to analyze and compare the inscriptions, while benefitting from the skills and knowledge I acquired during my bachelor’s degree in classical archaeology and ancient Greek at Tel Aviv University. I delved into the microscopic details of these inscriptions written by people from the First Temple period, from routine issues such as orders concerning the movement of soldiers and the supply of wine, oil and flour, through correspondence with neighboring fortresses, to orders that reached the Tel Arad fortress from the high ranks of the Judahite military system. I had the feeling that the time stood still and there was no gap of 2,600 years between the writers of the ostraca and ourselves.”

Combining forces between the human eye and the algorithm

Gerber explains: “Handwriting is made up of unconscious habit patterns. The handwriting identification is based on the principle that these

writing patterns are unique to each person and no two people write exactly alike. It is also assumed that repetitions of the same text or characters by the same writer are not exactly identical and one can define a range of natural handwriting variations specific to each one. Thus, the forensic handwriting analysis aims at tracking features corresponding to specific individuals, and concluding whether a single or rather different authors wrote the given documents. The examination process is divided into three steps: analysis, comparison, and evaluation. The analysis includes a detailed examination of every single inscription, according various features, such as the spacing between letters, their proportions, slant, etc. The comparison is based upon the aforementioned features across various handwritings. In addition, consistent patterns, common for different inscriptions, are identified i.e., the same combinations of letters, words, punctuation, etc. Finally, an evaluation of identicalness or distinctiveness of the writers is made. It should be noted that according to an Israel Supreme Court ruling, a person can be convicted of a crime based on the opinion of a forensic handwriting expert.”

Says Dr. Shaus: “We were in for a big surprise: Yana identified more authors than our algorithms did. It must be understood that currently, our algorithms are of a “cautious” nature – they know how to identify cases in which the texts were written by people with significantly different writing; in other cases they refrain from definite conclusions. Contrastingly, an expert in handwriting analysis knows not only how to spot the differences between writers more accurately, but in some cases may also arrive at the conclusion that several texts were actually written by a single person. Naturally, in terms of consequences, it is very interesting to see who the authors are. Thanks to the findings, we were able to construct an entire flowchart of the correspondence concerning the military fortress – who wrote to whom and regarding what matter”. This reflects the chain of command within the Judahite army.

“For example, in the area of Arad, close to the border between the kingdoms of Judah and Edom, there was a military force whose soldiers are referred to as “Kittiyim” in the inscriptions, most likely Greek mercenaries. Someone, probably their Judahite commander or liaison officer, requested provisions for the Kittiyim unit. He writes to the quartermaster of the fortress in Arad ‘give the Kittiyim flour, bread, wine’ and so on. Now, thanks to the identification of the handwriting, we can say with high probability that there was not only one Judahite commander writing, but at least four different ones. It is conceivable that each time another officer was sent to join the patrol – they took turns.”

Literary education in the Kingdom of Judah

According to the researchers, the findings shed new light on Judahite society on the eve of the destruction of the First Temple – and on the setting of the compilation of biblical texts. “It should be remembered that this was a small outpost, one of a series of outposts on the southern border of the kingdom of Judah,” says Dr. Sober. “Since we found at least 12 different authors out of 18 texts in total, we can conclude that there was a high level of literacy throughout the entire kingdom. The commanding ranks and liaison officers at the outpost, and even the quartermaster Eliashib and his deputy, Nahum, were literate. Someone had to teach them how to read and write, so we must assume the existence of an appropriate educational system in Judah at the end of the First Temple period. This, of course, does not mean that there was almost universal literacy as there is today, but it seems that significant portions of the residents of the kingdom of Judah were literate. This is important to the discussion on the composition of biblical texts. If there were only two or three people in the whole kingdom who could read and write, then it is unlikely that complex texts would have been composed.”

“Whoever wrote the biblical works did not do so for us, so that we could read them after 2,600 years, they did so in order to promote the ideological messages of the time,” Prof. Finkelstein says. “There are different opinions regarding the date of the composition of biblical texts. Some scholars suggest that many of the historical texts in the Bible – from Joshua to II Kings – were written at the end of the 7th century BC, that is, very close to the period of the Arad ostraca. It is important to ask who these texts were written for. According to one view, there were events in which the few people who could read and write stood before the illiterate public and read texts out to them. A high literacy rate in Judah puts things into a different light.”

Prof. Finkelstein adds: “Until now, the discussion of literacy in the kingdom of Judah has been based on circular arguments, that is, on what is written within the Bible itself, for example on scribes in the kingdom. We have shifted the discussion to an empirical perspective. If in a remote place like Tel Arad there was, over a short period of time, a minimum of 12 authors of 18 inscriptions, out of the population of Judah which is estimated to have been no more than 120,000 people, it means that literacy was not the exclusive domain of a handful of royal scribes in Jerusalem. The quartermaster from the Tel Arad outpost also had the ability to read and appreciate them.”

Featured image: Hebrew ostraca from Arad

Prof. Israel Finkelstein at a TAU dig in Megido

“The innovative technique can be used in other cases, both in the Land of Israel and beyond. Our innovative tool enables handwriting comparison and can establish the number of authors in a given corpus,” adds Faigenbaum-Golovin.

The new research follows up from the findings of the group’s 2016 study, which indicated widespread literacy in the kingdom of Judah a century and a half to two centuries later, circa 600 BCE. For that study, the group developed a novel algorithm with which they estimated the minimal number of writers involved in composing ostraca unearthed at the desert fortress of Arad. That investigation concluded that at least six writers composed the 18 inscriptions that were examined.

“It seems that during these two centuries that passed between the composition of the Samaria and the Arad corpora, there was an increase in literacy rates within the population of the Hebrew kingdoms,” Dr. Shaus says. “Our previous research paved the way for the current study. We enhanced our previously developed methodology, which sought the minimum number of writers, and introduced new statistical tools to establish a maximum likelihood estimate for the number of hands in a corpus.”

Prof. Israel Finkelstein at a TAU dig in Megido

“The innovative technique can be used in other cases, both in the Land of Israel and beyond. Our innovative tool enables handwriting comparison and can establish the number of authors in a given corpus,” adds Faigenbaum-Golovin.

The new research follows up from the findings of the group’s 2016 study, which indicated widespread literacy in the kingdom of Judah a century and a half to two centuries later, circa 600 BCE. For that study, the group developed a novel algorithm with which they estimated the minimal number of writers involved in composing ostraca unearthed at the desert fortress of Arad. That investigation concluded that at least six writers composed the 18 inscriptions that were examined.

“It seems that during these two centuries that passed between the composition of the Samaria and the Arad corpora, there was an increase in literacy rates within the population of the Hebrew kingdoms,” Dr. Shaus says. “Our previous research paved the way for the current study. We enhanced our previously developed methodology, which sought the minimum number of writers, and introduced new statistical tools to establish a maximum likelihood estimate for the number of hands in a corpus.”

“What’s more, cow husbandry requires grass and water, so it is very likely that cow hide was not processed in the desert but was brought to the Qumran caves from another place. This finding bears crucial significance, because the cowhide fragments came from two different copies of the Book of Jeremiah, reflecting different versions of the book, which stray from the biblical text as we know it today.”

Prof. Mizrahi further explains, “Since late antiquity, there has been almost complete uniformity of the biblical text. A Torah scroll in a synagogue in Kiev would be virtually identical to one in Sydney, down to the letter. By contrast, in Qumran we find in the very same cave different versions of the same book. But, in each case, one must ask: Is the textual ‘pluriformity,’ as we call it, yet another peculiar characteristic of the sectarian group whose writings were found in the Qumran caves? Or does it reflect a broader feature, shared by the rest of Jewish society of the period? The ancient DNA proves that two copies of Jeremiah, textually different from each other, were brought from outside the Judean Desert. This fact suggests that the concept of scriptural authority — emanating from the perception of biblical texts as a record of the Divine Word — was different in this period from that which dominated after the destruction of the Second Temple. In the formative age of classical Judaism and nascent Christianity, the polemic between Jewish sects and movements was focused on the ‘correct’ interpretation of the text, not its wording or exact linguistic form.”

“What’s more, cow husbandry requires grass and water, so it is very likely that cow hide was not processed in the desert but was brought to the Qumran caves from another place. This finding bears crucial significance, because the cowhide fragments came from two different copies of the Book of Jeremiah, reflecting different versions of the book, which stray from the biblical text as we know it today.”

Prof. Mizrahi further explains, “Since late antiquity, there has been almost complete uniformity of the biblical text. A Torah scroll in a synagogue in Kiev would be virtually identical to one in Sydney, down to the letter. By contrast, in Qumran we find in the very same cave different versions of the same book. But, in each case, one must ask: Is the textual ‘pluriformity,’ as we call it, yet another peculiar characteristic of the sectarian group whose writings were found in the Qumran caves? Or does it reflect a broader feature, shared by the rest of Jewish society of the period? The ancient DNA proves that two copies of Jeremiah, textually different from each other, were brought from outside the Judean Desert. This fact suggests that the concept of scriptural authority — emanating from the perception of biblical texts as a record of the Divine Word — was different in this period from that which dominated after the destruction of the Second Temple. In the formative age of classical Judaism and nascent Christianity, the polemic between Jewish sects and movements was focused on the ‘correct’ interpretation of the text, not its wording or exact linguistic form.”