By Lindsey Zemler

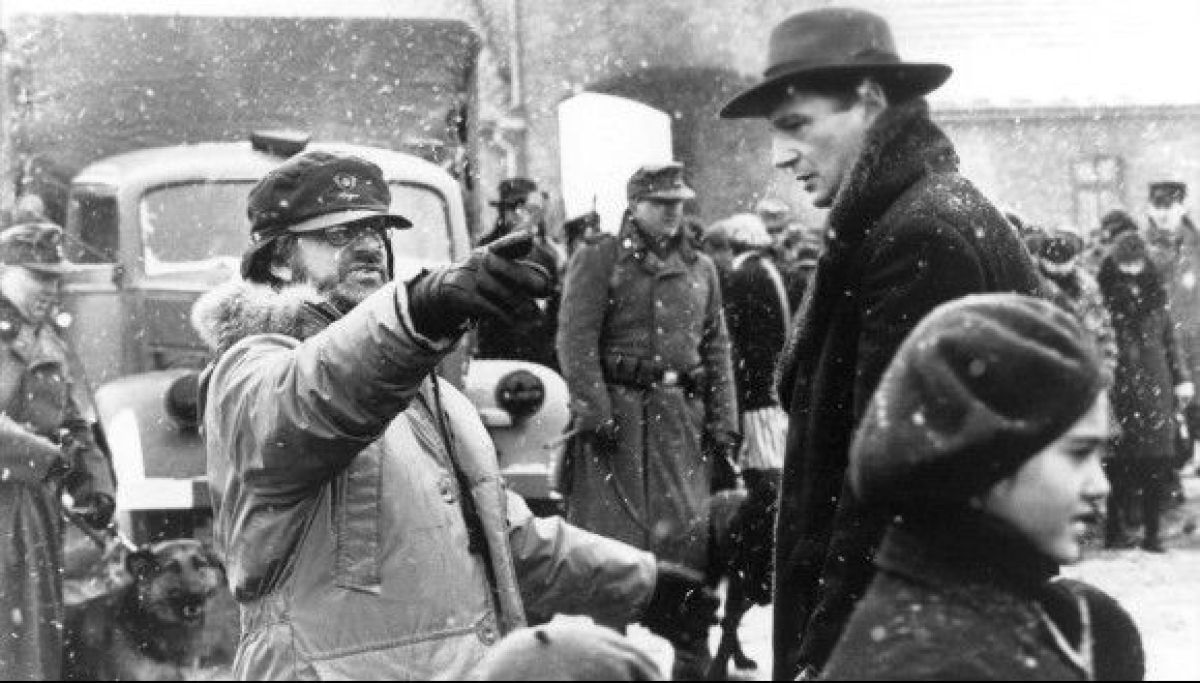

Schindler’s List is a classic representation of the Holocaust film genre because it represents the seminal historical event through an “iconic,” or heroic, figure, according to TAU PhD candidate Yael Mazor. Mazor, a lecturer at the Steve Tisch School of Film and Television, explains that alongside traditional portrayals of the Holocaust, we must leave space for new interpretations to keep the discourse about it alive.

Mazor and fellow film student Mooki Toren are among several TAU researchers whose fresh perspectives on the Holocaust are broadening the conversation on the watershed event.

It is crucial today, as the number of survivors dwindles, to “shape new ways to remember,” says Mazor. “One day, film will become the primary way to understand the Holocaust.”

“Film has always played a significant role in bringing history to the forefront, but there was a long time that it wasn’t acceptable to deal with the Holocaust in cinema at all,” says Mazor. “Eventually, in the 70s-80s, it became a popularized film genre, and more films on the subject were made, especially in Hollywood and Europe.” The definition of acceptable ways to represent the Holocaust has evolved with each passing decade, she says.

Mazor’s research on German cinema includes numerous examples of breaking convention when it comes to Holocaust films. Among them, she cites Phoenix (2014) which addressed Jewish identity in post-war Germany in an unprecedented way, thus leading to a better understanding of Germans’ memorialization of the War. Other films, such as Radical Evil (2013) and Downfall (2004) have been criticized for representing the perspective of or humanizing the Nazis. However, Mazor says that this controversial approach is important because it helps us understand how ordinary people become mass murders.

Photo: Researcher Yael Mazor.

Mazor’s interest in the Holocaust and German cinema stems from personal experience. Her father was a diplomat, and as a young child she spent several years living in Germany. Upon her return to Israel, she noticed that, for most Israelis, the primary association with Germany is the Holocaust.

“I observed that my personal associations with Germany, after living amongst Germans, are different from the collective memory of the Israeli people,” she explains. To this end, she is interested in how films both serve as indicators of how countries deal with their past and affect national cultural perceptions.

“Undoubtedly, the Holocaust is one of the most extreme events in human history, reaching the limits of our comprehension,” says Prof. Eran Neuman, Dean of TAU’s Yolanda and David Katz Faculty of the Arts. “The arts attempt to make it more understandable, using various representations such as extensive imagery, moving images, and spatial representation. It is this diversity that makes the intersection of art and Holocaust so interesting.”

Similarly, Mazor says that TAU’s institutional identity encourages “out-of-the-box thinking” and this is what allows TAU researchers, from the Tisch School and beyond, to refresh the discourse in their respective fields.

Photo: Researcher Mooki Toren.

Mooki Toren, also a Ph.D. candidate at the Tisch School, examines indirect representations of trauma and the Holocaust. His research proposes that although most of director Roman Polanski’s films do not belong to the Holocaust genre, they are highly influenced by his experience as a Holocaust survivor. Like Mazor, Toren’s interest in the topic is not coincidental; his mother was born in Berlin and her family fled Germany for Israel in 1936. “Sometimes I am haunted by the notion that I owe my personal existence to the Nazis, because otherwise my mother wouldn’t have met my father, who was born in Israel,” he says.

Toren explains that filmmakers face a challenge in finding the best way to represent traumatic events; even if they don’t address the Holocaust directly, they can use visual imagery. For example, The Lamp portrays a puppet workshop burning down as a metaphor for the world watching the abandonment of children with indifference. “This imagery leads us to the conclusion that there is no hope in a world in which the Holocaust was possible. It signals a warning that this can happen again.”

Ultimately, both Mazor’s and Toren’s are significant in rethinking the conversation on the Holocaust. Mazor’s analysis of German films goes beyond labels of “offensive” or “unacceptable” to consider what valuable perspectives were brought forward by films that were shunned by the mainstream. Toren’s new approach to methodically analysis of a single filmmaker’s work sets a precedent for further study of films not within the Holocaust genre can represent the Holocaust.

Prof. Raz Yosef, Head of the Tisch School, reinforces the importance of film and the arts in Holocaust memory. “The Holocaust is not representable in its unfathomable, inhuman enormity and yet it is a horror we have a duty to convey to new generations and protect from oblivion, denial, politicization and trivialization,” Yosef explains.

Toren goes one step further. “Memorializing the Holocaust through film can function as a call to action to ensure that it doesn’t happen again,” he says.

Featured image: Director Steven Spielberg with cast on the film set of Schindler’s List (1993).